Version French

A Broken Dream: The Reality of Eritrea

The Illusion of Freedom

Living in Arbaminch City, I witnessed a delegation from the Eritrean Provisional Government arrive to observe the referendum for independence voting. These votes were contentious, with the choice being framed as between slavery and freedom—a stark and somewhat implausible dichotomy. If the choice had been between independence and remaining with Ethiopia, perhaps some would have opted to stay. However, given the limited option, 99% of Eritreans chose independence, having fought for 30 years to be free from oppression. For Eritreans, independence was paramount, outweighing any relationships with Sudan, Yemen, Djibouti or Ethiopia.

At that time, the fervor for independence was palpable. Eritreans, having endured severe hardships under the Derg regime (Old Ethiopian Gov), were eager to support their government. The desire for freedom pushed us beyond our limits, fostering a belief that Eritrea was a new, untainted, and pure nation. Additionally, they warned Eritreans living in Ethiopia that without an Eritrean ID card, they would receive no protection from potential harm by Ethiopians. The dissemination of threatening propaganda spurred people to urgently obtain ID cards, regardless of their personal feelings.

During the referendum preparations, the Eritrean interim government issued temporary identity cards. As a university student, I intended to obtain my Eritrean ID. Despite being Eritrean by birth, I needed three witnesses to verify my identity on the spot. After a thorough investigation of my parents’ origins, I was deemed eligible for the ID. However, as students, my friend and I could not afford the 5 Ethiopian birr fee for the ID. We eventually sold my favorite jacket to gather the necessary funds, finally securing our Eritrean identity cards.

Encounters in Addis Ababa

Before the referendum, I attended a meeting with an Eritrean cadre at the embassy in Addis Ababa. During the discussion, a woman expressed concern about potential attacks by Ethiopians during the referendum voting. The cadre reassured her that an Eritrean commando team, stationed at Asmara Airport, could take control of Addis Ababa within an hour. I left the meeting astonished at such claims. Among Eritreans in Addis Ababa, faith in the Shabia force (Eritrean Gov force) was immense, fueled by the interim government’s unrealistic propaganda. The regime typically keeps its citizens and soldiers uninformed, allowing it to manipulate situations as needed.

Traveling to Eritrea

By the time I decided to travel to Eritrea at the end of 1996, I was working as an engineer in Mekelle City, Ethiopia. The situation in Mekelle was tense due to the strained relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Some Eritreans had been found dead in Mekelle, with no one taking responsibility for their deaths. Fearing for my safety, instead of going back to Addis, I chose to leave the city and head to Eritrea. Initially, I was alone, but soon, some of my family members were deported from Ethiopia and joined me in Asmara.

The journey to Asmara involved taking minibusses and making short trips from city to city. I traveled from Mekelle to Adigrat, then from Adigrat to Seneafe, and finally from Seneafe to Asmara. While waiting for a bus in Seneafe, I noticed a peculiar man following me from bar to bar. At the time, I didn’t realize he was a security agent. Eventually, the bus began boarding passengers, and I was the first to get on. The same man who had been following me sat right next to me. When I accidentally touched his chest while lifting my right hand, I felt a pistol under his jacket. Suspecting he was a security agent, we traveled together to Asmara, sitting side by side.

As we arrived in Dekemehare city, he started a conversation, asking if I spoke Tigrigna and if I was Eritrean. He wanted to know where I was going and why. I explained everything to him, and he listened attentively. He spoke Amharic fluently and asked about my profession and destination. Once we reached Asmara, he bid me farewell, and I headed to my aunt’s house, where I would stay for the next six months.

The next morning, I had an appointment with the organization that had called me for employment. As I approached the office early in the morning, I saw the same man standing in front of the building. He noticed me from a distance and turned to urinate on some flowers, which surprised me, given the presence of other people nearby. Later, I saw the man walking towards the exit door without greeting me. Despite this bizarre behavior, I completed my registration as a new employee and returned to the city for lunch.

While eating, the same man entered the restaurant and called my name. Astonished, I asked how he knew I was there and if he was following me. He replied, “No, I work around here.” I finished my lunch and left. The next day, I returned to the same restaurant, and once again, he appeared shortly after I arrived and greeted me. This continued for more than three weeks. I became increasingly frustrated and fearful, realizing he was deliberately following me. I had no one to help me except my relatives, who were incapable of assisting in such a situation. My mind began to conjure up scenarios that didn’t exist in reality.

One day, he approached me again, and I angrily asked if he knew me previously and why he was following me. He told me to calm down and invited me for coffee after lunch, which I refused. After lunch, I went to a coffee bar and ordered a coffee. While sipping my coffee, the man appeared again. Furious, I wanted to leave, but he told me to calm down and explained that he was a security agent. He had been following me from the Ethiopian border until that day, but now, he had confirmed my innocence.

I understand that there was also someone else secretly following me. If I entered any bar without the first man seeing me, he would still come to the bar and say hello. This suggests that someone else was secretly watching me and passing on information to him. I guess it was a team effort.

He revealed that I had been suspected of being a member of an opposition group operating in Ethiopia. Now that I was cleared, he congratulated me and assured me that there would be no more surveillance. He even invited me to his home to meet his wife. I was mesmerized by the circumstances and the open surveillance I had experienced.

Entering Eritrea at the border

Upon entering Eritrea at the border, Eritreans were interrogated in a separate room, while non-Eritreans received a white paper with a limited stay period, similar to a visa, in another room. Eritreans were questioned extensively about their destination, relatives, and the purpose of their travel. Secretly, a security agent would be assigned to follow them. Astonishingly, it was not the Ethiopians the authorities in Eritrea feared; it was the Eritreans themselves, hence the rationale for the tight surveillance. This was my first experience entering Eritrea, and it left a lasting impression on me.

The Harsh Reality in Eritrea

Being in Eritrea, I was confronted with a starkly different reality. The commandos I expected to see are nowhere to be found. The soldiers appeared malnourished and weak, unable to carry their weapons properly. When I inquired about the famous commandos I had heard of in Addis Ababa, I was arrested and tortured by a military camp leader named Janhoy in Halhale village. Tied to a tree and brutally beaten, I was devastated by the barbaric and illegal behavior. My eagerness to serve my country as a professional was crushed by this brutality, leaving me feeling hopeless and as though I had traveled back to a primitive, oppressive time.

When I returned to Asmara and recounted the events in Halhal to my superiors, their response took me aback. ‘They could have killed you,’ they said, almost nonchalantly. I was stunned by their reaction.

More than my civilian experiences, my time in the military at SAWA exposed me to the brutality of Eritrea. During the Third Ethiopian-Eritrean War, I was chosen to walk on mines as a human minesweeper. This is how it happened: from where we slept, around twelve trainees were selected and prepared to sweep the mines. We were expected to roll over the mines, causing them to explode, so others could follow safely. In their opinion, we were expendable and were told to be ready to die. It was deeply painful to be labeled as useless or worthless by these people. By the grace of God, the vehicle meant to transport us never arrived. The Ethiopian army pushed the Eritrean forces back, saving us from that terrible fate.

The Eritrea I had imagined was vastly different from the chaotic, disorganized reality I encountered. The ability of this disorganized group to defeat the well-organized army of the previous Ethiopian regime remains a mystery.

Life in Assab City

Military service in Assab City revealed a dire situation. We were served stale milk powder donated from Germany and unclean food. One particularly unhealthy meal was “bojboj” a communal dish where bread was broken and mixed on a large plate, often with minimal nutritional value. This eating method, intended to promote camaraderie, often resulted in health issues due to poor hygiene practices. The extreme heat, lack of proper sanitation, and the spread of disease further compounded our suffering. I contracted severe dysentery and was bedridden for three months.

The rigid, uninformed leadership ignored the dire conditions, enforcing communal eating despite the health risks. Attempts to improve hygiene were often met with punishment, reflecting the ignorance and stubbornness of the authorities.

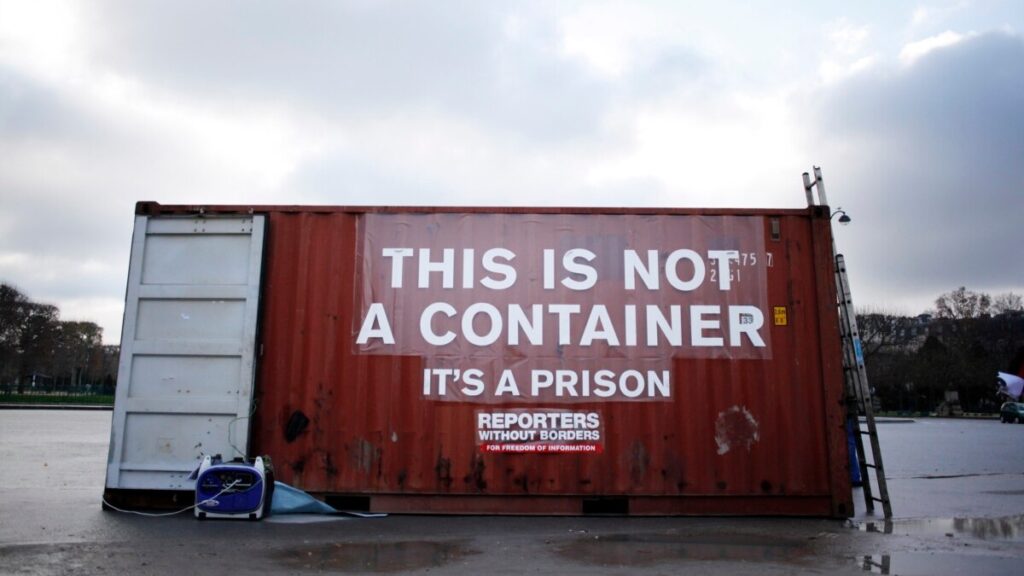

Assab Prison

One day, we traveled to Assab City with the colonel in charge of our unit. His destination was the Assab military prison, and he took me along. Upon arrival, he went into the office he needed to visit while I stood at the door, taking in my surroundings.

What I saw was shocking. A tall, muscular man was whipping a young man bound by iron chains. The young man’s legs were shackled, and he was bent over by his neck. The temperature was over 40 degrees Celsius, and he was covered in sweat, crying and sobbing. My heart ached for him, and I wondered what he could have possibly done to deserve such a cruel punishment. I had never seen or heard of such violence being inflicted on another person, and it disturbed me deeply. The pity I felt tormented my soul, and I wished to leave that country as soon as possible.

Later, the colonel returned, and we headed back to our camp. Unable to contain my anxiety, I asked the colonel about the punishment I had witnessed. I expressed my feelings about the young man. The colonel replied, “Severe punishments are given to those who fail to obey the law.” Then he reassured me, “Don’t worry, as long as you obey the law, you won’t be punished like this.”

In my opinion, this type of punishment is not educational. In fact It seemed designed to kill rather than to teach.

The True Face of Shabia (Eritrean Gov)

Over time, I realized that the propaganda-fueled image of Shabia was far from reality. Even Eritreans in Asmara were misled, believing their government to be infallible. It was only through national service that the true brutality and incompetence of the leaders became apparent. The regime, marked by corruption, lack of education, and moral bankruptcy, resembled a primitive, oppressive society.

The 30-year struggle was not for the people’s freedom but for the personal gains of a few. This regime systematically tortured, killed, and exploited Eritreans while misleading the diaspora for support. The emotional diaspora community, unaware of the atrocities, continued to support the government. It would be accurate to say that the main cause of the atrocities committed during the previous regime was the Shabia itself. Therefore, it would be correct to say that fighting the Shabia instead of the Derg (Old Ethiopian Gov) would have contributed to peace.

The Disillusionment

Returning from my dream, I saw Eritrea’s civil and military structures plagued by corruption and incompetence. Illiterate officials managed highly educated professionals and the oppressive regime monitored and brutally controlled its citizens. The world moved forward while Eritrea remained stuck in a cycle of fear, oppression, and deception. The dream of freedom was buried under this harsh reality, revealing a system that abused its citizens for personal gain.

Conclusion

The reality of Eritrea shattered all my illusions. The brutal regime forced citizens into violence against each other, highlighting the psychological crisis within society. The government’s moral decay and personal gain-driven actions made it clear that living without a country was better than enduring such abuse. Eritrea’s dream of independence was tragically taken away and replaced by a system of fear and oppression.

Divora (pen name)

Recycling any Metal including old cars. Comparing Benin (west Africa) & Ethiopia

Unprecedented Euphoria: Celebrations Ignite the Streets of Asmara

The Eritrean government has power over asylum seekers in Europe thanks to its spy network,especially the interpreters

If there’s one lesson from Isayas's rule, it's the importance of collective decision-making for a nation's progress.

ድንበር የሌለው ዲክታቶር ይሉሃል ይሄ ነው