From Expendable to Escaped: A Journey of Survival

A story continued from the previous one (click here to read the earlier story)

From Expendable to Escaped: A Journey of Survival

Military service at SAWA exposed me to horrors beyond imagination. The worst was being selected as a human mine sweeper, forced to walk over mines to clear the path for others. Labeled as expendable, I faced the constant threat of death, but by God’s grace, I survived. After enduring such cruelty, I knew I had to escape Eritrea and head for Sudan. The country had plunged into lawlessness, with leaders who had no respect for human life. There was no freedom, no space for thought or speech—only desperation.

Soon after, we were ordered to march toward Nakfa as Ethiopian forces gained ground, defeating the Eritrean army. We were told to carry a kilo of sugar and fill our containers with water for the journey into the northern mountains of Eritrea, where the struggle had begun decades earlier. After a day’s march, we rested briefly, only to be forced to continue. Exhausted, my legs blistered, and my water depleted, I collapsed, left behind, drained of all strength.

A young man named Kemal, a Muslim, approached me and offered help. He mixed milk with stream water from my backpack to make a drink, and we rested together until the afternoon. Kemal suggested I take a bath in the stream and introduced me to an older man nearby. The old man, who spoke only Tigre, offered us barley powder mixed with water and sugar, which helped me regain some strength. I learned that the old man was planning to return to Sudan that night, where he lived, having only visited family in Eritrea. Desperate for a way out, I decided to trust them and follow.

As we set off toward Sudan, Kemal acted as a translator. I carried a small radio, an organ, 500 Nakfa, and a gold necklace worth 1,400 Nakfa. The old man asked for the gold, and I gave it to him along with the 500 Nakfa, trusting them to guide me to safety. He noticed my Bible and warned that revealing my Christian faith could get me killed. He threw away my Bible and sleeping bag, giving me a white Tigre robe (djellaba) and instructing me to pretend to be deaf if questioned.

That night, we stayed in a village where we were given food and a place to sleep. Fear gnawed at me—what if they turned on me? Though the thought seemed far-fetched, the threat of being killed for my faith loomed large. The next morning, we continued our journey. The old man, experienced and resourceful, would often stop, smell the air, and dig for water under the sand. He provided us with dates and coffee as we traveled through the scorching desert.

After several days, we reached the border town of Kesela. We encountered others traveling at night, moving silently through the darkness during our journey. I wondered if they were jihadists or simply accustomed to traveling in the cool of the night.

The day before reaching Kesela, we rested in a forest, drinking coffee and recovering from our exhausting trek. As night fell, we resumed our journey, alert and anxious. The old man warned us to walk cautiously as we approached an Eritrean military post at the border. But to my shock, he led us straight into the camp of the Eritrean border soldiers. I couldn’t shake the feeling that he had done it deliberately to capture me. The soldiers searched me, found a military uniform in my bag, and questioned why I was leaving. My companions were allowed to go without being questioned or searched, but I was ordered to stay, becoming their prisoner.

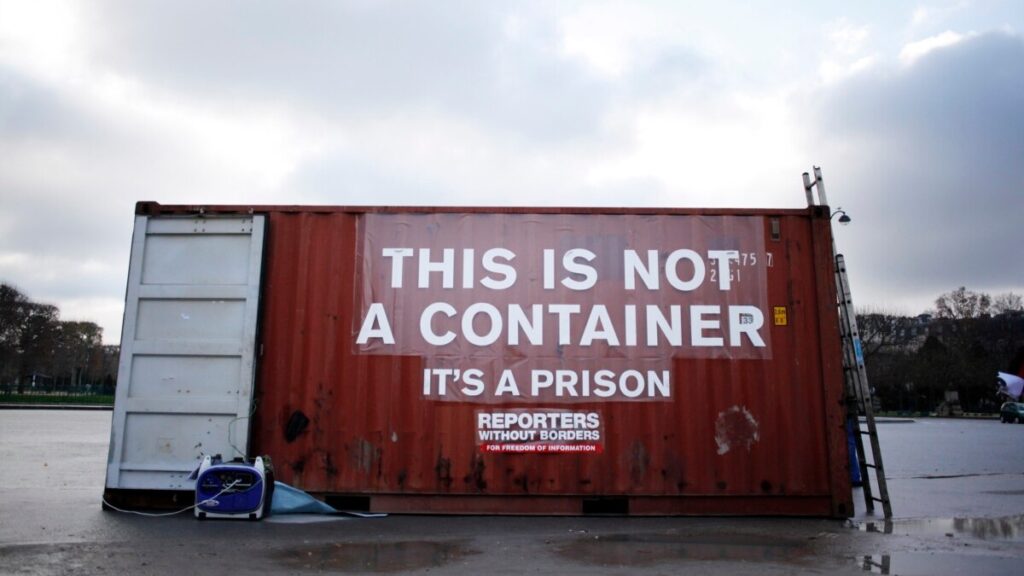

For a week, I was held by the border guards, unsure of my fate. Eventually, they put me on a military vehicle headed north to Girmaika, with a heavily armed guard. After a day’s travel, we arrived at a military camp where I overheard the guards discussing my status as a prisoner. The next day, a small Toyota Hilux took us to a prison near SAWA. I saw a quiet, eerie compound, later learning from an inmate that the cells were underground, keeping the prisoners’ suffering hidden. Most of us were interrogated; those who had fled the war zone to Sudan were told to remain, while I, as a trainee, was sent to SAWA’s 6th Brigade prison—less harsh by their standards.

At SAWA, I was placed in a small, overcrowded corrugated iron cell, barely 4 by 3 meters, with 3-meter-high corrugated iron walls. It was crammed with prisoners, including a few who were mentally unstable. We were let out twice a day for bathroom breaks and lunch, but the food was scarce—a single piece of bread most days. We were used as labor, filling water tanks, constructing mud huts, and cleaning cafeterias and offices. The prisoners in the other room were shackled with iron chains and were not allowed to work or leave the cell except for bathroom breaks. During these moments, working in the officers’ quarters, I scavenged leftover food just to survive.

One day, the prison boss, a colonel, asked if anyone could cut hair. I volunteered, seeing it as an opportunity to earn some favor. As I cut his hair, he asked about my story, and I told him how I had been left behind during a march and captured while trying to survive. Moved by my plight, he called the officers who had imprisoned me and ordered them to release me immediately.

I was sent back to my military unit in Hawashait. Upon my arrival, I was met with suspicion and hostility. The colonel checked my background and confirmed I was Eritrean, born to Eritrean parents. When asked why I had left for Sudan, I explained my situation. A friend vouched for me, and I was allowed to rejoin my group. But that night, the unit heads had decided to execute me as an example to others, labeling me a draft dodger. However, the colonel’s unexpected order to let me mingle with the group saved my life. The very night I could have been killed, I was spared by sheer luck.

Not long after, I was sent to the war zone near Assab, known for its intense heat and brutal conditions—a punishment for my perceived disloyalty. The journey to Assab was perilous, and there was fierce fighting between Ethiopian and Eritrean forces for 11 consecutive days, with heavy casualties on both sides. Despite the Eritrean government’s hopelessness, gallant fighters refused to abandon the city, defending it against capture.

On the way to Assab, we spent a night under a bridge in Dogali Village before being taken to the Massawa naval base to embark on another sea voyage. However, the ship was at Assab, and there was no other transport available. We spent five days at the naval base, loading and unloading ships, mostly with wheat and powdered milk provided as aid from Germany. Finally, the ship arrived from Assab, and we embarked on the 36-hour journey to Assab port by sea. Upon our arrival, the day coincided with the agreement between the unelected Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki and Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in Algeria, brokered by President Bouteflika, to cease the war. Then the decision was made: instead of sending us to the war zone, they gathered us in a school camp, separating professionals from non-professionals. I was chosen to remain in the city and work in the military construction industry, while others were sent to the front. Fortunately, the war had ended, and I served two years in the military as a site engineer, laborer, and guard, until I was released temporarily in 2002.

In the meantime, I had the opportunity, after one year of service, to settle my civilian life and gather my personal belongings, as it was not intended for me to stay more than one month in military service. The military also decided to keep me for more years as the construction work we started took more than 10 years. That was why the colonel sent me to settle my affairs in Asmara and return, as I had left all my personal belongings in my rented house. I had to settle those affairs in two months and returned to Assab. While in Asmara, during the break, I worked in a friend’s company and earned some extra money that could help in the months to come. I had no money to stay in Asmara; I used to sleep in my friend’s office or in hotels. The money came unexpectedly from friends or from working. National Service in Eritrea had no salary. It paid 50 Nakfa, equivalent to today’s not more than 3 dollars per month. It was on this trip that I met Kemal again, the man who had led me to Sudan. He was enjoying a drink at a bar in Massawa. When I asked him what had happened after the soldiers caught us at the Kesela border, he casually replied that he had returned and continued his life as usual. It became clear to me that everything had been orchestrated—a drama to entrap me. Yet, my innocence had saved me.

Leaving the Country for South Africa

This was how it happened: The University of Asmara sent a letter to the central command at Assab, requesting the release of a few graduates to return to Asmara, and I was one of them. Only two of us were allowed to leave the Assab front and eventually permitted to leave the country. However, leaving was not easy; I faced endless bureaucracy, mischief, and obstacles. My unit head gave me only two months to settle my affairs in Asmara, holding onto my military records to keep me tethered. With the help of authorities, I was finally released from military service temporarily and allowed to travel to South Africa. The expectation was that I would return to serve in the military after completing my studies in South Africa as a national serviceman.

What began with me being labeled expendable, and forced to walk over mines, ended with me narrowly escaping death, both from unforeseen circumstances and my countrymen. The Eritrea I once imagined to be a country had become a place of unimaginable hardship and betrayal, leaving me forever changed.

Divora (Pen Name)

Are they being used as tourist attractions?

Analyzing Success and Failure: The Triumph of Biniam Girmay and the Downfall of the Sahel School.

When an Idiot President gives lectures at the Kenyan summit, as he did in Eritrea and Russia

ድንበር የሌለው ዲክታቶር ይሉሃል ይሄ ነው